01 Dec Tokyo – the old amongst the ultra new

It’s August and Tokyo’s in the midst of its annual heat wave. I’m sucking on ice cubes from my matcha tea, staring out the window at a garden so perfect that the window feels like a still life painting. Stones are perfectly laid for stepping over a pond; tree leaves are sculpted into round bunches – like green lollipops.

We’re relishing the air conditioning in an ancient feudal lord’s home. During the Edo period, before Tokyo was the capital, the families of the feudal lords lived in these traditional homes. The lords were forced to live in the country during the week, and commute back home on the weekends to be with their families. The government thought it was a good way to keep the small towns alive. Interestingly enough, centuries later, many of these small towns are dying. Sadly, no one wants to live in the traditional Japanese homes anymore. In fact, there are almost 5 million abandoned ‘minka’ homes throughout the country—a few years ago it was declared a national crisis.

Sitting cross legged at the table, I love that there isn’t much ‘stuff’ in the room—a few long tables on the woven ‘tatami’ mat floor, and slippers lined up perfectly in the ‘genkan.’ It’s also quiet, save for the occasional swoosh sound when you open the rice paper doors.

One of only three surviving feudal lord gardens in Tokyo—Korakuen Gardens is named after a poem encouraging the ruler Mito to enjoy his pleasure only after he’s achieved happiness for his people.

Outside, I see a little girl with her mom. Dressed in her school uniform, she resembles a young Anne of Green Gables with a straw hat and long skirt.

“Why are Japanese so obsessed with Anne of Green Gables?” I ask Carlos, my Japanese bike guide—a name he inherited from living in Brazil.

Carlos Googles, “Anne of Green Gables, Japan”. “The book was on Japan’s school reading list for juniors in 1972.” He pauses. “Six years later it was made into an animated movie.”

We postulate about other reasons for the Anne obsession – including a longing for wide open spaces and nature, both which are hard to find in a crowded city of over 9-million.

I’m done with destroying my liver in Tokyo’s Shibuya party zone – a place where tourists can pay a $30 entrance fee to a robot bar, or watch poorly behaved drunk salarymen (the nick name for overworked men who wear mandatory black and white and work incessantly).

I’m cycling through Tokyo’s lesser-known, more traditional, neighbourhoods in the northeast. This garden is a mental breath-of-fresh-air.

Koishikawa is one of a handful of neighbourhoods that remained intact after a major fire in 1923, the Allied bombings of World War II, and a major earth quake.

Carlos’ partner, Yukiko, owns Tokyo Great Cycling Tour (https://www.tokyocycling.jp) and the three of us have been cycling all day in this heat. The theme of our bike tour is Old World Tokyo. We start in the morning at Nihonbashi bridge. The original bridge dates back to 1603, but it was rebuilt to accommodate street cars. Its guarding lions are reminiscent of another time. In 1945 the area around the bridge was destroyed in the single largest air raid bombing in history. It’s also the point from which all distances in the country are measured to Tokyo– it’s the zero-kilometer marker.

Today, there’s a giant set of Olympic rings beside the bridge – Toyko is the host of the 2020 games.

I’ve been cycling through Japan for almost three months now (bike camping). In most respects, Japan, and the Japanese, are organized and proper when it comes to rules. But when it comes to cycling in the city, rules schmules. Bikes are permitted on sidewalks and no one goes in the same direction. It’s like fish moving around a rock in a stream, but it works; cyclists can be heading straight for you, then glide by at the last second without flinching.

I follow behind Yukiko, as she snaps right and left through residential back alleys. Eventually we stop at a Zoshigaya Cemetery.

“Everyone in Japan is cremated, except for the Emperor,” says Carlos, while looking out onto the crypts. Indeed. Japan has the highest cremation rate in the world – for mostly practical reasons: lack of space. Japan’s total land mass is less than 4 percent of the United States. With 127 million people it makes sense to conserve space.

Before I continue, I must tell you about a must-visit neighbourhood, to which will add relevance to this story! Hold tight.

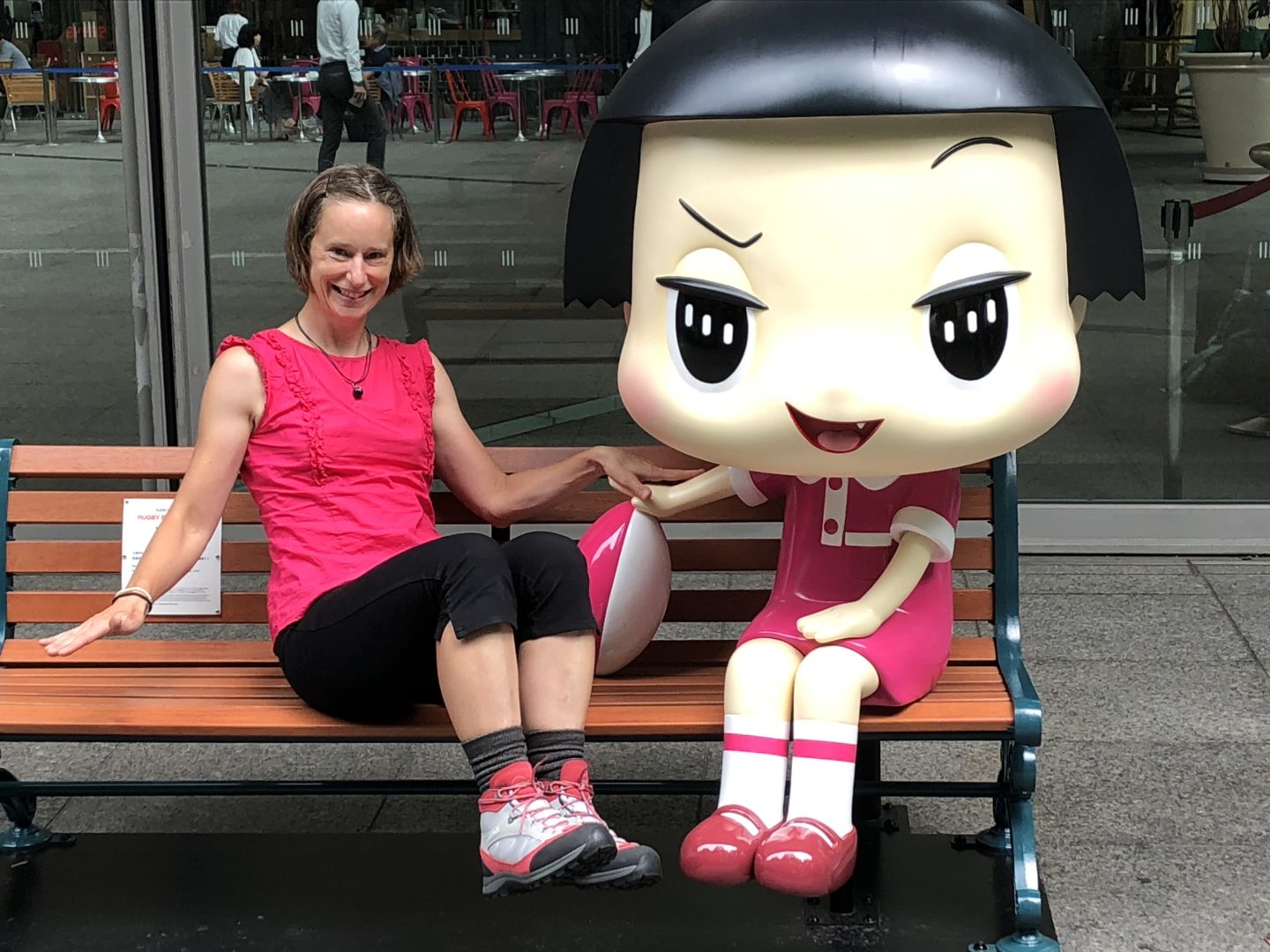

Harajuku is a district in the Shibuya neighbourhood; it’s known for kawaii- cute. (this isn’t part of our bike tour – I visited earlier).

This includes a store that sells things to squish (little teddy bears, or plastic toast); or, rainbow coloured grilled cheese, or a themed cartoons. My favourite is an animated egg yolk character. “Gudetama” or ‘gude gude’ which, in Japanese, means lazy and tired. A tired egg yolk! Are you getting this? The cute egg yolk appears on candy boxes, electrical cords, tin foil, etc… my favourite was him on a tissue box- he was laying in bed with a piece of bacon as a blanket. Cute! [And a little bizarre?]

Ok, so the point of me telling you about Harajuku? Our next stop, Sugamo Togenuki Jizo,is a Shopping Street dubbed the Harajuku for old people. In Jizo, lingerie shops carry primarily red underwear—the elderly believe that red is a sign of strength and power; red granny panties.

The Jizo neighbourhood is tranquil compared with Harajuku. It’s more sweet shops and clothing stores geared towards grannies. I spot a place selling homemade mochi – my absolute favourite thing to eat in Japan. Made from rice flour, the exterior is gelatinous and squishy; inside is sweet bean curd. You can buy them in 6 packs at the 7/11 – in plastic wrap with preservatives, they can last forever. But, these ones at the bakery in Jizo are fresh. Its gooey texture and sweet filling don’t make sense; it reminds me of the kawaii stuff—that doesn’t make sense either, but it is adorable, silly and heart warming. Mochi is gooey and delightful. Try saying the word mochi without giggling. I dare you.

The Jizo neighbourhood is tranquil compared with Harajuku. It’s more sweet shops and clothing stores geared towards grannies. I spot a place selling homemade mochi – my absolute favourite thing to eat in Japan. Made from rice flour, the exterior is gelatinous and squishy; inside is sweet bean curd. You can buy them in 6 packs at the 7/11 – in plastic wrap with preservatives, they can last forever. But, these ones at the bakery in Jizo are fresh. Its gooey texture and sweet filling don’t make sense; it reminds me of the kawaii stuff—that doesn’t make sense either, but it is adorable, silly and heart warming. Mochi is gooey and delightful. Try saying the word mochi without giggling. I dare you.

Next to the shopping street, we visit a temple. Kishimojin is the deity of children who used to eat babies before Buddha hid one of her kids, forcing her to see the error of her ways. Many temples in Japan are a mix of Buddhism and Shinto (which believes that every living thing has a soul; I agree). Carlos explains the two Shinto lions at the entrance to the shrine: one’s mouth is closed while the other’s is open — “one is for birth when you open your mouth wide and say, ahhh.

The other one is closed because when you die you say, mmm, and close your mouth.”

The other one is closed because when you die you say, mmm, and close your mouth.”

Like layers of leaves in the fall, the layers of Japanese tradition and history cover the city.

We climb a small hill to our final destination – Gokokuji temple. Entirely wooden, it’s one of the few remaining ancient temples not destroyed in Tokyo’s tumultuous past. Dating from 1681, it was home to the Tokugawa family that ruled Japan in the Edo Period 1603-1868 – Edo is the former name of Tokyo, which was renamed Tokyo when the shogunate era ended. Around the property you can still find original plaques written by Tokugawa Tsunayoshi, the fifth shogun.

Today, it’s eerily quiet. Few travellers know about this place.

Walking down the stone steps lined with lush azalea flowers, we find an elder man sweeping the walkway near a giant stone basin. He tells Carlos how he used to hide in the basin when he was a child. He’s 80-years-old. The Tokyo of his childhood is vastly different than today.

From the temple, the skyline is modern, space age; and yet, on these moss-covered steps, surrounded by perfectly shaped hedges, this is the Japanese of my childhood story books.

No Comments